PFAS are everywhere. Removing them from the Cape’s water supply will not be easy.

Cape Cod Times

Beth Treffeisen

March 2, 2023

BOURNE — Rose Forbes, 56, a pollution cleanup manager for the U.S. Air Force on Joint Base Cape Cod, slowly drove her compact SUV toward the entrance of the Otis Rotary in Bourne on a rainy October day.

“I hate this rotary,” she said, wary of entering it.

There were two tanker rollovers near the site — where she spends an extensive amount of time doing research.

Fire prevention efforts at the crash sites let loose PFAS, known as the forever chemical, that seeped into the aquifer below, polluting nearby private wells. Cleaning up those chemicals is the focus of Forbes’ work. But the problem of PFAS pollution is much bigger and includes us all, town and military officials say.

Thousand of gallons of fuel spilled in Otis Rotary

In the early morning on Sept. 19, 1997, a truck driver heading south on Route 28 to meet the ferry to Martha’s Vineyard lost control of the 18-wheeler in thick, heavy fog. He hit the curbside on the edge of the rotary, across from the Joint Base Cape Cod entrance, which caused the tanker to flip on its side.

The truck was carrying 5,500 gallons of gasoline, and about 3,000 gallons spilled from the truck into the roadway, flowing into the nearby drainage system and seeping into the ground, the Cape Cod Times reported at the time.

Three years later, it happened again. A new recruit training with the U.S. Army Reserve was behind the wheel of a tractor-trailer filled with 7,200 gallons of jet fuel. He was going too fast when he entered the rotary.

“He couldn’t negotiate the curve and boom, right in the center there,” Forbes said, pointing at the grassy area in the middle of the rotary.

About 300 gallons of jet fuel spilled out of the tanker, onto the rotary, and into a nearby pond. An aerial photograph of the scene shows the tanker lying on its side, splattered with foam used to prevent a fire, known as aqueous film-forming foams or AFFF.

EPA proposes regulations on two types of PFAS

Unbeknownst to the firefighters using the foam during these crashes, it contained chemicals of emerging concern: PFAS.

Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, are a group of thousands of synthetic chemicals that have been in use since the 1940s, according to the federal Environmental Protection Agency.

In August 2022, the EPA proposed designating the two widely used forever chemicals, perfluorooctanoic acid, or PFOA and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid, or PFOS, as hazardous substances under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act, better known as the Superfund.

Reports show that various consumer and industrial products use the chemicals, from nonstick pans to stain-resistant carpets and upholstery — and firefighter protective gear.

While there is currently not enough evidence pinpointing that a specific level of exposure leads to adverse health effects, studies show that continued exposure to PFAS may lead to several health problems, including immune system issues, increased cholesterol, cancer, thyroid hormone disruption, and decreased vaccine response in children, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Two decades after the two tanker rollover crashes, Forbes is still cleaning up the mess.

The PFAS found in the AFFF fire foam used to clean up the tanker rollovers traveled in the aquifer underground about two miles away to wells used by private homes on Valley Farm Road in Cataumet.

Researchers studying connection between PFAS exposure and heath problems

Geoffrey Pedersen has lived in the family house on Valley Farm Road, which had a private drinking water well, since 2010

“There’s really not much to say,” he said of the PFAS pollution. “We’ve been drinking it for years.”

Pedersen’s mother and stepfather lived in the house and drank the water until they left in 2006.

“My mother died of kidney cancer. Whether that was a factor or not, it’s hard to say,” Pedersen said.

“There are certainly people who feel their health has been affected by PFAS exposures,” said Laurel Schaider, a senior scientist at Silent Spring Institute, a nonprofit organization dedicated to studying environmental health-related topics. “At a population level, you can say ‘yes, this population, in general, has a higher risk’ and say that someone might be more likely to suffer from a certain disease.”

PFAS in lobsters? :Another sign these harmful compounds are everywhere, researchers say

However, many health effects associated with PFAS exposure are also common to other factors, Schaider said. For example, linking one apparent environmental factor to a health outcome for mesothelioma is far easier — asbestos exposure clearly links to lung disease. But “for PFAS, it can be really difficult to make that linkage.”

Research is ongoing. The Silent Spring Insitute is currently recruiting people who lived in Hyannis between 2006 and 2016 — and children whose mothers lived in Hyannis during that time — and may have been exposed to PFAS to participate in a five-year study that got underway in 2021.

(People interested in participating in the Hyannis study can sign up on the Silent Spring website, or by calling 508-296-4298.)

PFAS found in private, municipal water supplies across Cape Cod

In 2010, Silent Spring Institute researchers studied unregulated drinking water contaminants in public wells on Cape Cod, Schaider said. They found PFAS in nine public water supplies.

In a follow-up study between 2013 and 2015, researchers found that not only did Hyannis have higher levels of PFAS than other water supplies in the state, but blood samples of residents were in the top 1% tested across the country, Schaider said.

In March of 2022,18 firefighters from Fall River, Hyannis and Nantucket had blood samples drawn to measure the level of PFAS in their system, the Times reported in April. The small study tested how much of the cancer-causing “forever chemicals” in their gear rubbed off on their skin and entered their bloodstream. The early results are not encouraging.

For all the PFAS groups tested, the firefighters’ average is “above the national average,” said Ayesha Khan, co-founder of the Nantucket PFAS Action Group, to The Herald News in Fall River.

“It’s not groundbreaking, but it’s confirming the information that’s out there, which is part of good science,” Khan added. “Firefighters do in fact have higher levels of PFAS in their blood.”

Removing PFAS from water a difficult task

For scientists and municipal workers tasked with removing these forever chemicals, there are no easy options. Pumping out the chemicals from Cape Cod’s single-source aquifer is difficult, tedious, expensive, and seemingly endless because the chemicals continue to enter the environment, according to Forbes.

Testing and installing wells that pump up water from the aquifer through filters takes a long time. Even testing for PFAS is a protracted process. For example, it takes one to three days to drill a well. The drill goes down a few feet, takes a few samples, and continues until it hits the bedrock. Then, it can take years, if not decades, to remove the chemicals to safe drinking water standards, according to the EPA’s cleanup process.

Once the chemicals are removed from the environment, the PFAS, PFOA and PFOS chemical bonds are so strong it takes the equivalent of an act of lightning to destroy them, said Forbes — leaving very few options for anyone looking to get rid of the chemicals.

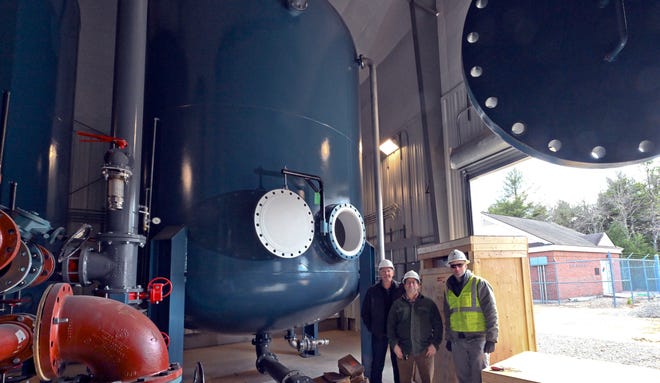

Unlike private wells, municipal water suppliers where PFAS have been found, such as the Hyannis Water District, use filters to remove the chemicals from drinking water before it gets to consumers.

PFAS found in multiple locations on Joint Base Cape Cod

About 14 years ago, Forbes’s team was working on a five-year review for the EPA when the agency asked that they begin testing for specific PFAS, PFOA and PFOS on the base where the fire-prevention foam was used. The EPA anticipated it would be present at some specific sites on the base.

“And sure enough, it was there,” Forbes said.

The scientists then began searching for PFAS at the obvious sites: the fire departments and aircraft hangars for the U.S. Coast Guard and Air Force. And then, her team looked at less obvious sites: the landfill and the wastewater treatment plant. All the sites had PFAS. It became apparent to Forbes that contamination was beyond the base’s boundaries.

However, one site, the fire training area used between 1958 and 1985, is the most significant source of PFAS due to the heavy use of the AFFF foam.

Tainted water: PFAS in Cape Cod water more widespread than previously known

“So, it’s not much to look at now, but back in the day, this is where the fire department did their training,” Forbes said. “They would have a mock aircraft and put that on fire or just right on the ground pour jet fuel in this pit that wasn’t lined. Anything that would burn they would just put on the ground and set on fire.”

Today it seems absurd to do this type of training, said Forbes. But, training was needed for people dealing with mechanical malfunctions of aircraft such as the F-15 or the Super Constellation aircraft, used during the Cold War, catching fire.

In the end, “the foam works,” Forbes said. “If you are in an aircraft fire, you want somebody using that AFFF foam because it works, but then, you want someone to clean it up afterward.”

The trainees sprayed the firefighting foam on everything, she said. The fire training area is vast, and the soil is contaminated. Figuring out where to put the contaminated soil is a big problem.

And it’s not just on the surface, she said. It goes 60 feet down.

Rain and melting snow carry chemicals in tainted soil down into the aquifer when it is carried through the water. The Cape’s sandy soil allows the chemicals to spread more quickly. The aquifer is the main source of drinking water on Cape Cod.

Bourne landfill works on solution to prevent PFAS contamination

Similarly, the Integrated Solid Waste Management facility, the only active landfill on the Cape, is also looking for ways to remove the chemicals, which can eventually reach the aquifer from seepage.

“You got to remember something, folks, we neither profit, generate, or use any of these products,” said Dan Barrett, the general manager at the landfill in Bourne, which borders the base to the west.

“We get them from society,” he said. “We get them from you. We’re passive receptors. Now, all of a sudden, we’re the fiends; we’re the people damned because we do this.”

PFAS pollution: Air Force agrees to pay for PFAS cleanups in Mashpee and Falmouth wells

Carbon filtration systems that take PFAS out of groundwater didn’t work well for landfill leachate (water that leaches through landfills and is collected for treatment) — “it clogs in like three seconds.”

So, the landfill began using liners made out of bentonite, a clay-like substance, which worked better. The only problem was that the landfill had to change the liners constantly. So, the team there kept looking for better solutions.

Forbes recommended a pretreatment process called surface-activated foam fractionation — or SAF for short — to the landfill team. Working with a company out of Australia, the landfill secured the equipment needed to see if it would work and the results exceeded their expectations.

Holding them accountable: Chatham joins at least two other Cape towns in PFAS lawsuit

The team is now finalizing plans to bring in the equipment full-time. The landfill secured about $1.3 million from the town of Bourne to move forward.

Everybody from the waste side of the business is dealing with PFAS, said Phil Goddard, the Manager of Facility Compliance and Technology Development at the landfill. Industries and utilities now are in the position of having to test and treat for it. Neither the state nor the federal government has regulations on PFAS from landfills, he said. But Goddard and Barrett think it is only a matter of time until the state and federal regulators set standards.

“This is big,” Goddard said. “It’s one of the biggest issues of the 21st century. We’re hearing from the federal level, and it is at the top of their list. Climate change, PFAS, is on the top of their list.”

Who should pay to remove water, soil PFAS pollution?

While PFAS cleanup is becoming more feasible, the costs of cleanup are just starting to be understood. Millions of dollars were already spent removing the chemicals in the towns bordering the base.

Although the residents of these towns are not footing the bill for that cleanup, “ultimately, the taxpayer” is paying for it through the federal government. “We’re talking millions of dollars here,” Forbes said.

“Somebody’s got to” cover the bill, said Forbes. “Surprisingly, our senior leadership didn’t push to make me go and try to get some cost recovery, although who knows, that might be in the future.”

Upper Cape PFAS pollution: Air Force updates PFAS water quality tests

The base also covered the cost in 2016, when scientists found PFAS in some of the private wells on Valley Farm Road. Eight wells were above the state’s safe drinking water standard, with the source being the two tanker rollover sites approximately two miles away.

Base officials first gave out bottled water. Then the government paid for and contracted whole-house filtration systems for several homes along Valley Farm Road, each costing about $6,000 to install, with additional costs for monitoring and maintenance.

Eventually, base officials agreed to connect the houses on Valley Farm Road to municipal water, which cost $888,285. The construction finished just last summer. One homeowner paid to connect their home because testing showed PFAS levels below safety levels. Therefore, the Air Force could not cover the cost.

What’s next for PFAS contamination on Cape Cod?

“It’s just not easy,” said Robert Lim, the program manager for the federal EPA in New England for nearly 30 years. He said the Air Force estimates that the cleanup at the tanker rollover sites will not be complete until 2140.

“It’s a chemical world,” Forbes said. “We use a lot of chemicals that aren’t well studied, that aren’t well regulated. The EPA only has so much time and personnel to evaluate the risks associated with these chemicals out there. I fully expect that there’ll be other PFAS-type issues in the future.”

Clean drinking water: As Barnstable hunts for new sources of public drinking water, PFAS contamination rears its ugly head

Once the chemicals enter the environment, there is no easy way to take them out. Schaider said, “they’re going to be there for a very long time, for generations.”

“We’ve created this pollution challenge,” she added. “We can take steps to minimize people’s exposures, but we can’t rein those chemicals back in.”

PFAS is everywhere, said Goddard.

“I think people are waking up to the real impact,” he said. “Logistically, financially, operationally, politically.”

Stay connected with Cape Cod news, sports, restaurants and breaking news. Download our free app.

PFAS are everywhere. Removing them from the Cape’s water supply will not be easy. – Cape Cod Times