Rising temperatures a boon for harmful bacteria in Cape Cod’s fresh and salt water

Cape Cod Times

Doug Fraser

Feb. 2, 2022

Here’s the difference between red tide and blue-green algae. Wochit

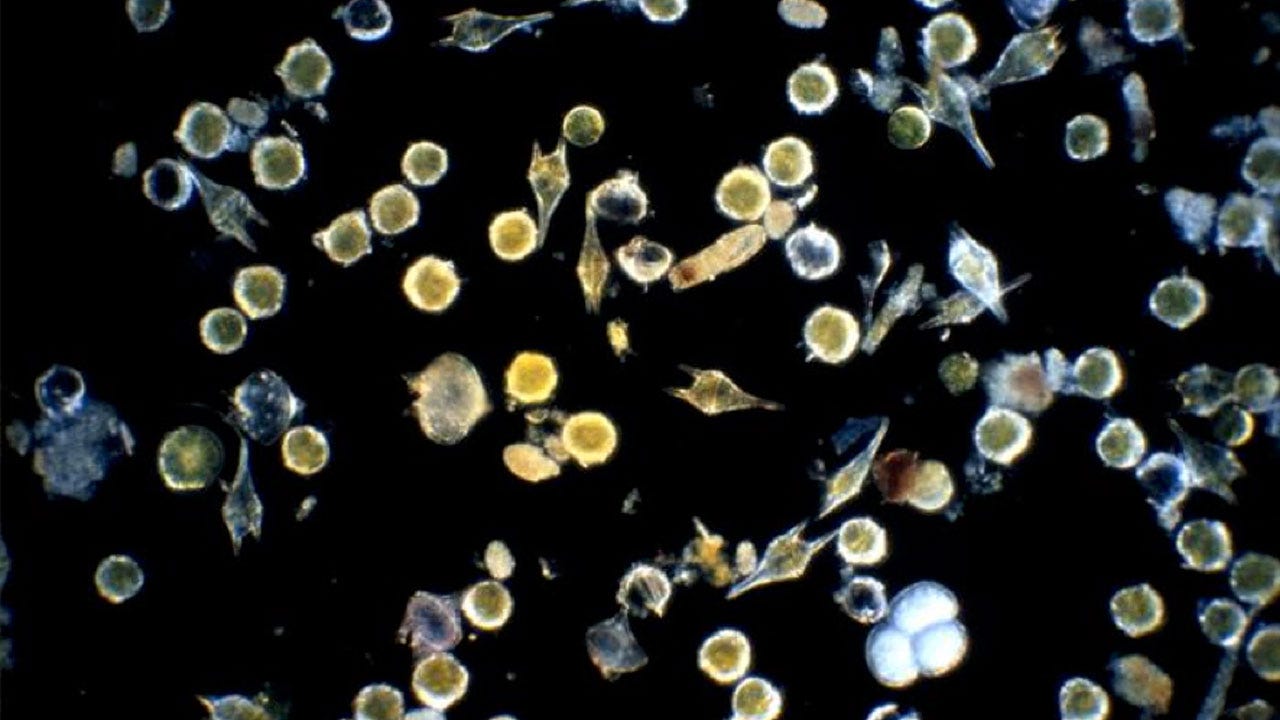

WOODS HOLE — The world depends on water to drink, to irrigate crops, for the seafood that feeds millions. As the earth’s population continues to grow, so has that dependence on water, but pollution and a warming planet are aiding the proliferation of harmful bacteria — true survivors dating back billions of years to the dawn of life on earth.

“This is a problem, that is truly getting worse,” said Don Anderson, a senior scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and director of the U.S. National Office for Harmful Algal Blooms. Located at WHOI, the national HAB office is the hub for coordinating research and communication about the problem both in the U.S. and internationally.

From the toxic scum on ponds and lakes to the nuisance blooms that can shut down vital desalination plants providing water to millions, the Cape Cod region — and the world, is increasingly tuned into the problems presented by Harmful Algal Blooms.

Risks from Harmful Algal Bloom

“HABs are significant due to the different kinds of risks they pose and the impacts they can have on human and aquatic health. Some HABs produce toxins that are dangerous to humans as well as wildlife, including marine mammals, fish, shellfish, and plants,” according to WHOI’s 2022 report, “Harmful Algal Blooms: Understanding the Threat and the Actions Being Taken to Address it.”

“Algal blooms that are non-toxic can still be very harmful due to their sheer mass and high density of cells, which can ultimately cause a broad array of ecosystem-wide impacts,” the report notes. HABs also can “disrupt drinking water supplies and cause severe economic impacts to fishery resources, aquaculture, and local recreation and tourism industries.”

Anderson has a framed copy of the 1998 Harmful Algal Bloom and Hypoxia Research and Control Act hung on his office wall. He pushed for its passage and has testified nine times before Congress to continue funding.

The act, and its subsequent amendments, requires the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the Environmental Protection Agency to advance scientific understanding, detection and prediction of HAB and hypoxia (when oxygen levels can’t support life) events in both marine and freshwater environments in the U.S. It created a task force and provided funding to develop ways to reduce the likelihood of these events and mitigate their damage.

Anderson said recent analysis found that globally there was no significant increase in harmful algal blooms because changing environmental conditions affect species in both positive and negative ways.

“We no longer say that they are increasing in frequency and magnitude globally. Now we say they are increasing in certain areas, while in other areas they are decreasing,” Anderson said. “Nevertheless it is so much bigger and diverse a problem than we thought it was decades ago.”

This is due, in part, to increased awareness and detection by organizations like the HAB office at WHOI and international organizations like GlobalHAB.

“The science is better, the communication is better,” Anderson said.

Early detection alerts researchers

WHOI and NOAA set up a warning system in the Gulf of Maine that includes automated technology on buoys that can detect the presence of red tide algae and alert researchers. Plus, research into currents and cyst beds where algae can lay dormant awaiting favorable conditions have helped to produce a predictive model for red tide blooms and impacts in the Gulf of Maine and North Pacific. Predictive models are also in place for other HAB hotspots like the Gulf of Mexico and the Great Lakes.

With greater detection, researchers are also aware of the role played by the natural dispersion of bacteria by global and localized currents. In 1987, hundreds were poisoned and three people died after eating shellfish harvested on Prince Edward Island, Canada. It stemmed from domoic acid, a potent toxin produced by the Pseudo-nitzschia plankton, a marine bacteria that was rarely seen in the Gulf of Maine, but suddenly showed up in 2016 and resulted in shellfish closures and recalls in Rhode Island and Buzzards Bay.

Global shipping is generally blamed for the introduction of invasive species, carried in ballast water or packing materials. But researchers believe that with HABs, the transport is most likely natural distribution. Anderson said the Pseudo-nitzschia probably came down from Canada, carried by an animal or a change in currents or more freshwater input that favors the species.

“Once here, it’s hard to flush it out. It becomes a resident,” he said.

‘Things are worse’: Cape Cod water quality is declining, says environmental group’s report

What is driving researchers now is the expansion of species in the Gulf of Maine that require research and mitigation.

“If you talked to me in the ’70s and ’80s, the only problem in the region was PSP (paralytic shellfish poisoning from toxins produced by red tide algae),” Anderson said.

Over the years other problems have emerged like Diarrhetic Shellfish Poisoning and Karenia mikimotoi, which can cause massive shellfish die-offs and is believed to have been responsible for the “dead zone” in Cape Cod Bay in recent years with low levels of oxygen, and Cochlodinium, a fast growing algae that has been found in Falmouth and can suck up all the oxygen, killing fish and shellfish on aquaculture farms.

But pollution and climate change remain a dominant factor, making conditions that are more favorable to the bacteria, Anderson said. Led by researchers from WHOI and NOAA, a team recently found that warming seas could cause a huge long-dormant cyst bed to germinate and release red tide algae into the waters off southeastern Alaska — that may have ecosystem-level impacts.

Cyanobacteria on the rise across Cape

On Cape Cod there has been a rise of cyanobacteria — an algae that produces toxins harmful to humans and animals — in lakes and ponds. The Association to Preserve Cape Cod recently started testing water quality and tracking cyanobacteria blooms in ponds and lakes. This past year, it found unacceptable water quality in 38 ponds and this summer cyanobacteria blooms in 31 ponds reached a level requiring closure.

“One consistent element affecting them all is warming,” said APCC Executive Director Andrew Gottlieb, and bacteria like warmer waters.

Researchers from Salem State University and the University of Massachusetts Amherst showed that between 1900 and 2020 New England already warmed past the 1.5 degrees Celsius mark set by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change as a benchmark to avoid drastic environmental changes.

Blue-green algae: Harmful cyanobacteria prompts summer beach closures from Rhode Island and Vermont to Ohio

A 2018 study of ponds in the Cape Cod National Seashore by National Park Service researchers showed two decades of increasing surface water temperatures. In a majority of the ponds they studied, summer thermoclines — layers determined by water temperature and density — had strengthened over time. This layering inhibits the mixing of oxygen from the surface into bottom layers, which then become oxygen-starved and can kill off marine life and vegetation.

These conditions promote the chemical exchange of phosphorus into the water that would otherwise be trapped in decaying leaf and other organic matter in bottom sediments. Along with phosphorus from lawn fertilizer and septic effluent, this natural source can promote the explosive growth of algae.

The Cape is attempting to deal with the nutrient pollution to freshwater and marine water bodies from the 85% of its homes and businesses that use septic systems. The nitrogen and phosphorus in the effluent acts like fertilizer for fast growing algae that can outcompete other aquatic vegetation.

“The linkage to pollution is hugely relevant to freshwater blooms. That is a true smoking gun,” Anderson said. “Cyanobacteria are extremely good competitors and they like hot sunny water.”

Last summer, the Mashpee board of health found that half of the 121 homes within 300 feet of Santuit Pond, which has been struggling with excess nutrients and cyanobacteria blooms, hadn’t had their septic systems or cesspools pumped within the past decade.

“What you are seeing on the Cape is decades of problems with septic systems,” said Anderson. Groundwater travels slowly and even if the entire Cape was sewered today and no more nitrogen or phosphorus entered groundwater, there is a big reservoir of nutrients that will reach ponds and marine embayments for decades to come and a lot more already stored in bottom sediments.

“Meanwhile the temperature is going up and these species are doing very well,” he said.

Contact Doug Fraser at dfraser@capecodonline.com. Follow him on Twitter: @DougFraserCCT.

https://www.capecodtimes.com/story/news/2022/02/02/warming-planet-a-boon-for-harmful-algae-cape-cod-fresh-and-salt-water/6515200001/